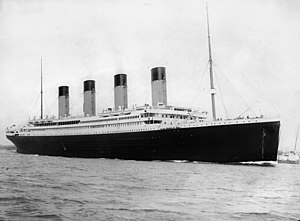

One hundred and three years ago today more than 1,500 people died in the freezing waters of the North Atlantic when RMS Titanic hit the iceberg and then sank, in the early hours of 15 April. My great-grandmother, Nöel Rothes, was one of the lucky survivors and this year YOU Magazine in the Mail on Sunday has printed an article I wrote about that terrible night, the things Nöel did to help the survivors and the bond she and the Able Seaman in charge of her lifeboat forged. You can read it here, if you’d like to. I also wrote about her and the tragic sinking on the 100th anniversary in 2012, here.

RMS Titanic leaving Southampton on 10 April 1912 (from Wikipedia)

The Dance of Love, my novel that reimagines Nöel’s life – as discussed here on the wonderful Shiny New Books – took a while to write, and to get right, partly because I’m a novice novelist (it’s my second) but also because it was my first piece of historical fiction so I didn’t recognise immediately, as Hilary Mantel so wisely put it:

You have to think what you owe to history, but you also have to think what you owe to the novel form. Your readers expect a story and they don’t want it to be two-dimensional, barely dramatised.

The Dance of Love doesn’t faithfully follow the course of my great-grandmother’s life: when an image arrived unbidden one day I realised the story I was writing was emotionally linked to that image and not to many of the facts that made up her real life.

The Dance of Love doesn’t faithfully follow the course of my great-grandmother’s life: when an image arrived unbidden one day I realised the story I was writing was emotionally linked to that image and not to many of the facts that made up her real life.

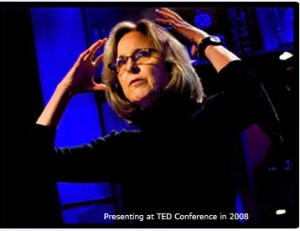

On 22 April my sister, Sue Tribolini, will interview me about things that arrive unbidden while writing. We’re going to talk about what isn’t anticipated, where these things might come from and how it might be possible to harness them. The station is called a2zen.fm, it’s based in Toronto and Sue’s Invisible Dimension show is an hour long.

Chekhov said: A writer is a person who has signed a contract with his conscience.

The Middle English translation of conscience is inner knowing; the Latin is with-knowing/understanding. Sue and I are going to see what we can untangle of this inner knowing and it would be lovely if you joined us here, at 8pm on 22 April (or, if you’re in the US or Canada: 12 noon Pacific; 1pm Mountain; 2pm Central or 3pm Eastern time).

Obviously these are stills, but if, when they’re in motion, they’re as glorious as

Obviously these are stills, but if, when they’re in motion, they’re as glorious as