Last weekend I walked through a wood. Sunlight filtered through the leaves and made me think how medieval stonemasons must have been inspired by the branches of trees gathered in arching vaults above them when they imagined their cathedrals. In a modern reversal, in Italy, near Bergamo, there’s a tree cathedral:

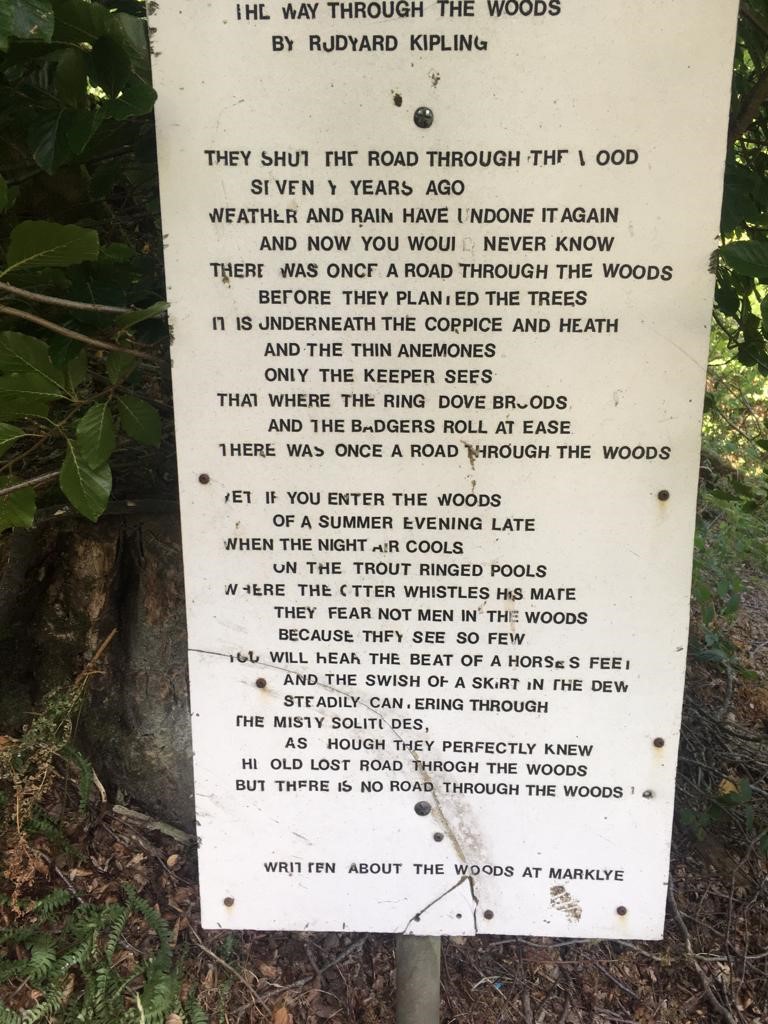

And, at the entrance to the particular wood where I was walking, this stands:

And, at the entrance to the particular wood where I was walking, this stands:

Some of the letters are worn away, but if you click on the image you’ll get to the Kipling Society’s site and their page for The Way Through The Woods.

Some of the letters are worn away, but if you click on the image you’ll get to the Kipling Society’s site and their page for The Way Through The Woods.

These things made me think about the things trees do – apart from providing shade and solitude and places to think and dream. In Richard Powers’ wonderful novel The Overstory Patricia Westerford shows us how trees communicate. Her character was inspired by the life and work of forest ecologist Suzanne Simard. Simard’s research into the way trees nurture each other, help the sick among them, promote growth and so much more is, literally, awe-inspiring. The things that go on beneath our feet about which we know so little. Simard’s book Finding the Mother Tree, Discovering the Wisdom of the Forest, is surely a must-read. Here’s a quote from her website:

Trees are not simply the source of timber or pulp, but are a complex, interdependent circle of life; forests are social, cooperative creatures connected through underground networks by which trees communicate their vitality and vulnerabilities. [They have] … communal lives not that different from our own.

How often we humans only think of trees as useful for us. How rarely we think about the lives of trees themselves, these days. But there’s a long association between innate wisdom and trees that’s filtered into our language, as Jay Griffiths writes, in Ancient Trees, Ancient Knowledge, here:

The English language recognizes an association between wisdom and trees: an idea ‘takes root’; a book has ‘leaves’; a small book is a ‘leaflet’; an avid reader is a ‘bookworm’; you ‘branch out’ into a new area of study … .

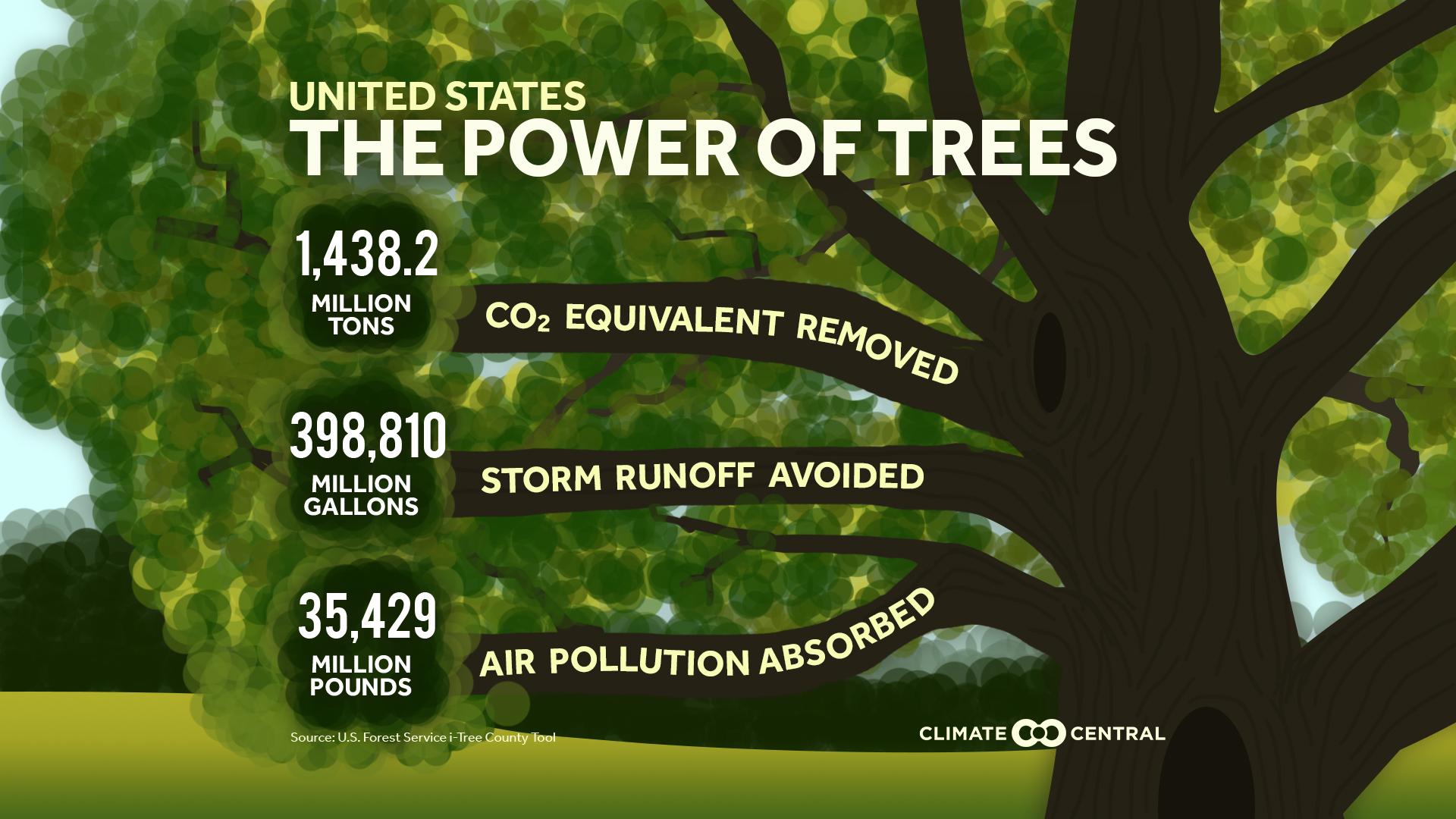

Some people make forest farms. Others categorise trees: here’s an alphabetical list of seventy-six types. Some people say that, when we’re about to judge the shape of another human, it would be better to think of that person as a tree: we never say a tree is too fat or too short or too thin or too tall, do we? Let alone too old. We admire trees, whatever their shape or age. And we all know by now what trees do to help fight climate change.

So it seems to me that we humans – the ones who don’t already – need to ask not what trees can do for us but what we can do for trees.

So it seems to me that we humans – the ones who don’t already – need to ask not what trees can do for us but what we can do for trees.

Leave a Reply