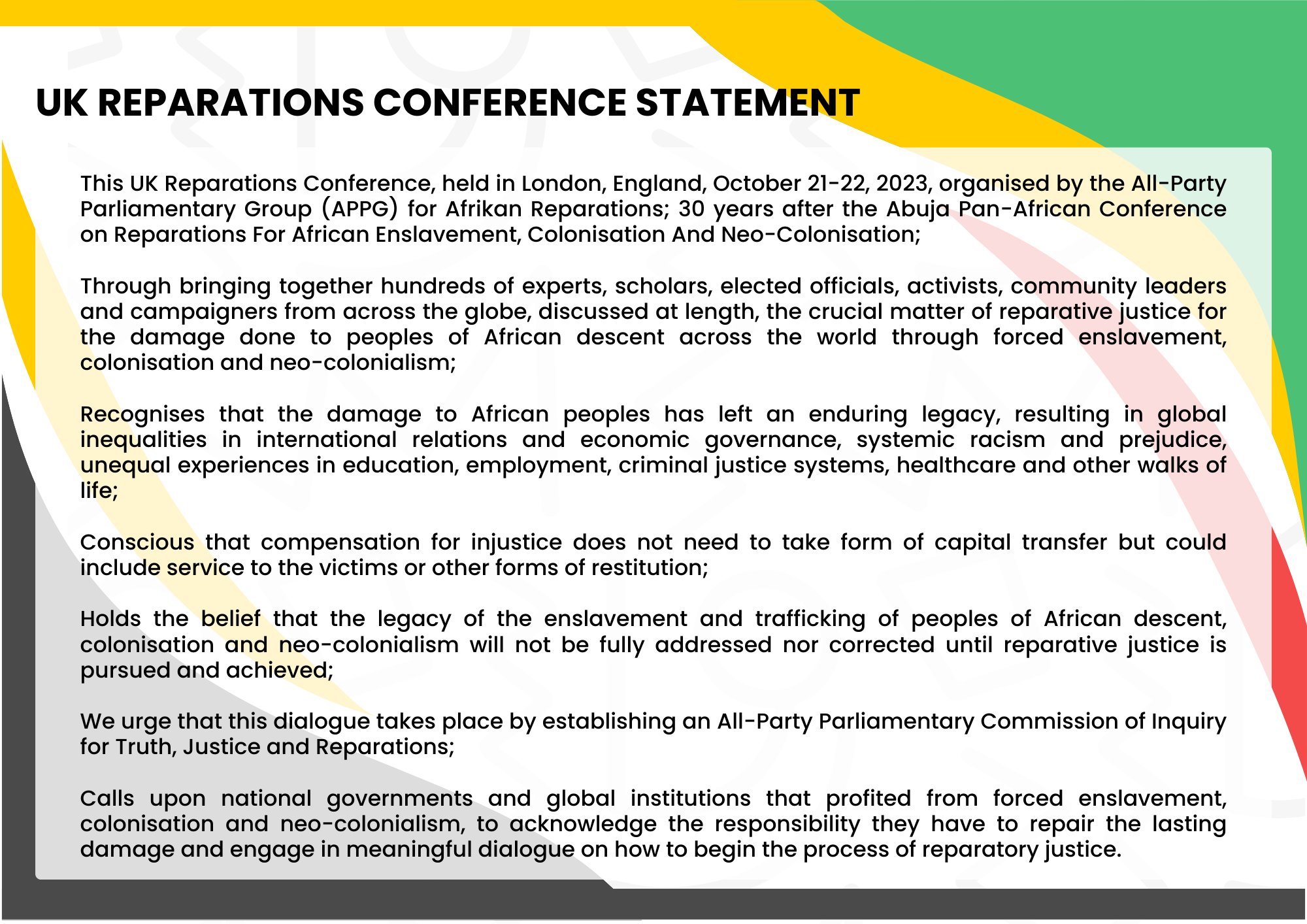

On Saturday 21st and Sunday 22nd October, in London, a conference to discuss Afrikan Reparations and to address the legacy of the trafficking and enslavement of peoples of Afrikan descent, of colonisation and colonialism, was held. I went, at the suggestion of the leader of the White Allies Network. I was humbled, informed, heart-broken and uplifted by what I heard.

When white people think about reparations or reparatory justice for people of colour, we tend to think about money. But although money is extremely important, it was rarely the first thing the speakers or delegates wanted.

This account of the conference doesn’t cover the vast array of subjects discussed, nor the rich and varied contributions made by the speakers and some of the delegates, because there were seventeen breakout sessions and each delegate could only choose four. But it is a digest of what I heard.

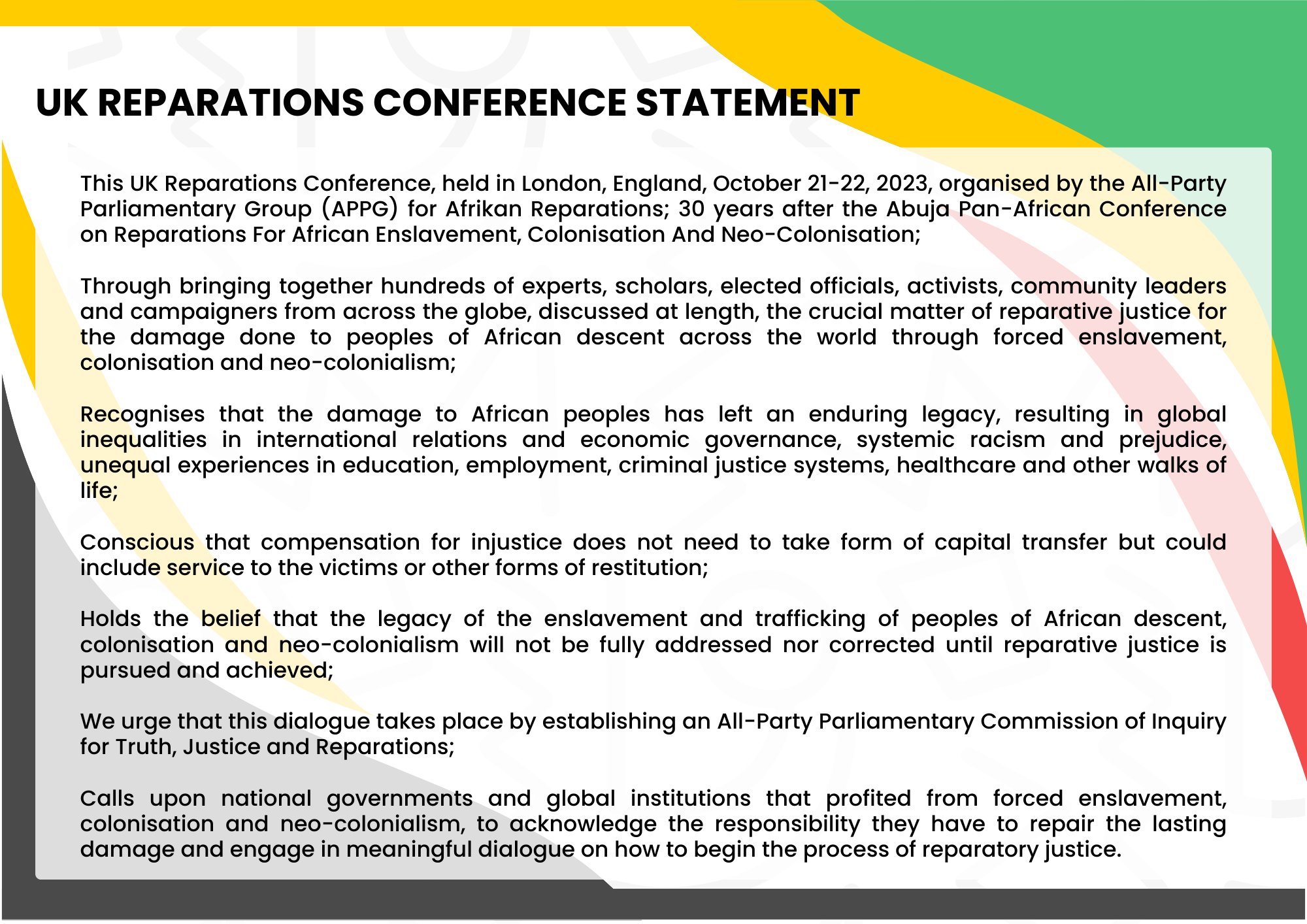

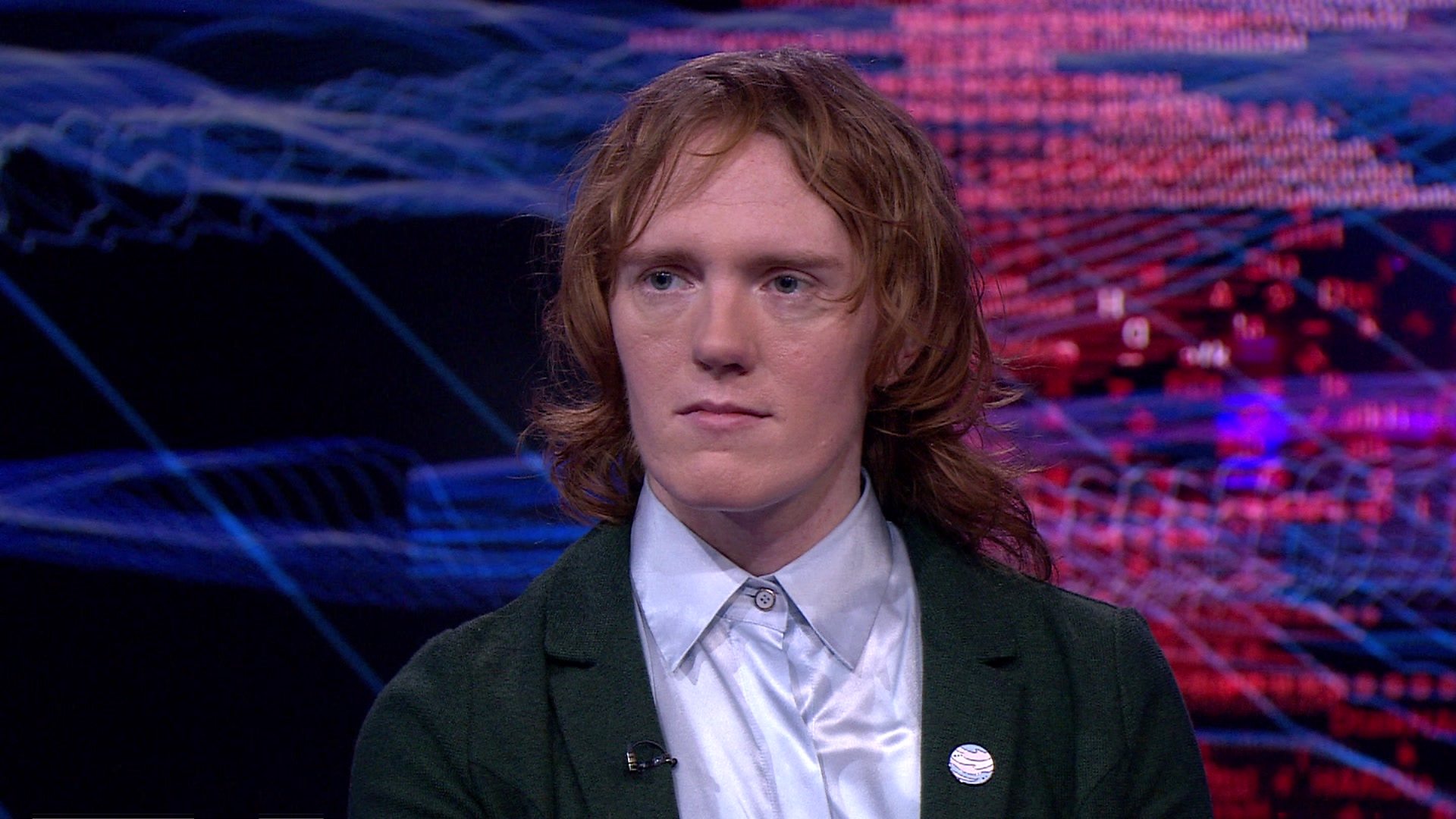

Bell Ribeiro-Addy, Labour MP for Streatham and chair of APPG-AR (the All Party Parliamentary Group for Afrikan Reparations who organised the conference) chaired the conference. She said, in an interview with the Guardian:

Reparative justice has to go much further [than financial compensation], it has to go towards equity, repairing all the damage that was done as a direct consequence of the trafficking and enslavement of Africans.

Bell Ribeiro-Addy, Labour MP for Streatham

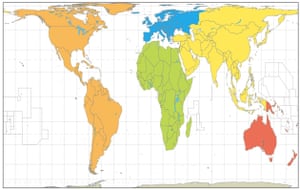

Each morning, in the main hall, djembe drummers welcomed us and accompanied the speakers. Each day opened with a plenary, followed by smaller breakout sessions. The subjects covered ranged from: the law and reparative justice to cultural redress; faith, NGOs and reparatory justice to pan-Afrikanism; women’s rights; media and social transformation; community regeneration; heirs and allies; environmental reparations; political economy and social enterprise; international relations and geopolitics; education; racial justice and intersectionality; and more.

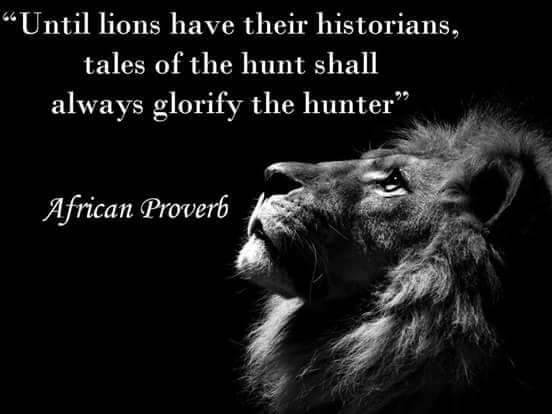

Many Black luminaries, young and old, spoke of the need for education of their own people about their own history before the damage could be undone. (There’s an agenda for the two days here which includes all the speakers’ names and titles. Diane Abbott was unable to attend the first day.)

Kimani Nehusi, a Professor at the Temple University College of Liberal Arts in Philadelphia, said:

If we don’t know how we suffered and how we continue to suffer, then we don’t know how to correct the damage.

Kobina Amokwandoh from the Pan-Afrikan Reparations Youth Forum said:

Everyone in this room has been miseducated … . There’s been historic opposition to us educating ourselves. We need that knowledge. We need to educate ourselves … . Young people around the world who look like me are killing each other because they don’t know who they are … . Education is preparation for reparations. Let each one teach one.

Education (and healthcare) was high on the list of essential reparations, education about Black history. On the second day, in the plenary session, the historian, Robin Walker told us how Afrikan expertise was stolen by white people. He said, ‘Enslavement didn’t just steal brawn, it stole brains.’ He said people of colour should know that Jack Daniels, Peter Rabbit, the combine harvester and the smallpox vaccination, to name a few, were all originally invented by Black people. But riches from these inventions have descended to white generations while poverty has descended to black generations because these inventions were attributed to white people when in fact they were invented by black people and appropriated by white people.

Professor Dr Maulana Karenga, founder of the annual end-of-year holiday, Kwanzaa, said:

We are injured physicians who have it within ourselves to heal ourselves. We are our own liberators. No matter how sincere our allies, we must liberate ourselves. It is our duty to know our past and honour it; to know our present and forge it; to know our future and [work for it].

On the first day, in the plenary, Esther Stanford-Xosei, of Stop the Maangamizi (the Afrikan Holocaust, the genocide of enslavement; the Kiswahili term for the continuum of chattel enslavement, colonialism and neocolonialism) demanded reparations ‘On behalf of our ancestors’. She also talked, as Kobina did, about the difficulty of demanding reparations when you don’t know your roots. She quoted Marcus Garvey: ‘A people without knowledge of their history and culture is like a tree without roots.’ She talked about the Maangamizi Educational Trust and how the Maangamizi must be named. She said, ‘History is the bedrock of everything we’re doing. But,’ she said, ‘historicide is being committed: the erasure of the illustrious works of our forebears.’ The education system in the UK must recognise the Maangamizi.

Discussing Cultural Redress, Wangui Wa Goro, Professor of Translation Practice at SOAS, said, ‘We lost our tongues [our languages] at the hands of the oppressor. So we lost the ability to remember … . We were removed from our cultural systems.’ She said Liberated Zones, little pockets of reparations and reparative justice must be created, through language. She urged delegates to learn at least one Afrikan language.

At a Community Regeneration session, Nana Kojo Bonsu [Kojo], a delegate, but also the man who led the libation and the blessing on the conference at the beginning of the first day, said land and access to the land is so important. He said, ‘Without land you can’t develop. The restoration and restitution of land is essential. Anyone who offers financial compensation and not land, doesn’t know what they’re talking about.’

At a session on environmental reparations, Maria Xochitl Tricks, said:

It’s impossible to talk about environmental justice without talking about cognitive and reparative justice.

She said, ‘We need to tackle climate change through system change – and reparatory justice.’ She said people must reclaim their land, and when they do that, or try to do that, it must be recognised that they’re not terrorists.

At the first plenary session, Kwami Kwei-Armah, Artistic Director of the Young Vic, talked about the importance of narrative. He said, ‘Narrative controls us, but Afrikans are perceived as inferior and the system supports this. This inferiority is bred into us. There’s a subconscious inferiority among black people.’ He grew up feeling ugly and that, he said, is narrative. ‘Narrative gives or takes power, gives or takes strength.’ He said enslaved people, after they landed on American shores, were ‘seasoned’, by the oppressor. He said, ‘They took away our names; they took away our culture; they took away our spirits; they took away our everything.’ He also said he wanted to make sure the reparations cause is fashionable, young, hot and revolutionary. To get and keep young Black people committed.

The Convenor of an education session, Preparation for Reparations, Dr Oli Harrison, said: ‘Schools in the UK are incapable of dealing with questions of reparatory justice [but] … we’re here today to bring forth the contradictions and to find harmony and ways forward towards reparative justice.’

Malik Al Nasir said, ‘Reparative Education must be taken [not given or requested].’ He said, ‘We need to work together to make a new approach to education. We need to popularise APPG-AR by lobbying our local MPs.’ And in the final plenary, among many other speakers, Esther Stanford-Xosei, who is also a member of the APPG-AR secretariat, said:

This project is not just financial – it’s an emancipatory and liberatory project. Reparations cannot be made only by a mere transfer of funds from the oppressor to the oppressed. Reparatory Justice must be driven by Afrikan Communities.

So, before money, came self-education and self-knowledge: Kobina’s, ‘Education is preparation for reparations’; education to counteract mis-education. Languages and narratives must be reclaimed; land must be restored; there must be equity and debt relief and the return of stolen artefacts and human remains. Governments must apologise for enslavement, and there must be financial reparations. For a sense of the reparations that were discussed at the breakout sessions I couldn’t attend, see the agenda.

Not everyone agreed on the order of reparations but, at the end of a Pan-Afrikanism session, a panellist said:

APPG-AR is the place where we can disagree collegiately – we need to create these spaces where we listen to each other and reason through our perspectives, if we are to become a force.

Appg-ar.org will be releasing footage from the conference soon. Here’s a link to videos of various conference sessions.

I’m sure the pursuit and enactment of these reparations will take time. But they must be enacted, if our world is to become a fairer, more equitable place.

Bell Ribeiro-Addy closed the conference with a vote of thanks to all who sponsored and supported it. She ended by reading the Conference Statement.

I didn’t realise shame and I had such a strong attachment until shame began to detach: until I began to feel more clearly, speak more clearly, hear and see more clearly, without shame blurring my focus and making constantly negative judgements. Until I began, as

I didn’t realise shame and I had such a strong attachment until shame began to detach: until I began to feel more clearly, speak more clearly, hear and see more clearly, without shame blurring my focus and making constantly negative judgements. Until I began, as